Train Mentors to Help Mentees Synthesize Information

About 20 years ago, I was sitting in the student section of a basketball game while an undergrad at the University of Notre Dame. We were locked in a tight battle with Syracuse and the Joyce Center was rocking. We fouled a Syracuse player late in the game, and as he stepped to the line to shoot two critical free throws, the decibel level in the building was deafening. The effect, however, was like loud white noise; the sound was loud but not distinct. The player calmly sank the two free throws and I turned to one of my roommates and exclaimed, “You know, constant sound is like silence, only louder.”

About 20 years ago, I was sitting in the student section of a basketball game while an undergrad at the University of Notre Dame. We were locked in a tight battle with Syracuse and the Joyce Center was rocking. We fouled a Syracuse player late in the game, and as he stepped to the line to shoot two critical free throws, the decibel level in the building was deafening. The effect, however, was like loud white noise; the sound was loud but not distinct. The player calmly sank the two free throws and I turned to one of my roommates and exclaimed, “You know, constant sound is like silence, only louder.”

The point I was making is that simply being loud was probably not significantly distracting to the opposing player. While there were thousands of people contributing to the noise, none of those individual sounds stood out and served as a distraction. Had the crowd been quiet and then even one person abruptly yelled right as the shot was being released, my guess is that would have increased the chance of the crowd’s desired result (i.e., a missed attempt).

Almost 20 years later, this memory recently came back to me as I was thinking about the plethora of “sound” or “noise” that most of us must filter through every day in order to simply do our jobs. How many times in the last month have you thought, uttered, or even outright exclaimed, “I receive too many $%&@# emails!” The volume of emails, returned search results, legitimate knowledge resources, etc. that pass in front of our eyes every day can be mind-boggling. How do we effectively filter through all of this noise so that we take notice of those things that we actually want to be distracted by? (Yes, being distracted can be a welcomed occurrence.)

One of the best things about the way most of us work is that we have ready access to an abundance of information that can help us do our jobs better. One of the worst things about the way most of us work is that we have ready access to an abundance of information that we don’t know what to do with. How do we effectively drink the quality single malt from the information superhighway without becoming drunk on the cheap stuff?

One of the best things about the way most of us work is that we have ready access to an abundance of information that can help us do our jobs better. One of the worst things about the way most of us work is that we have ready access to an abundance of information that we don’t know what to do with. How do we effectively drink the quality single malt from the information superhighway without becoming drunk on the cheap stuff?

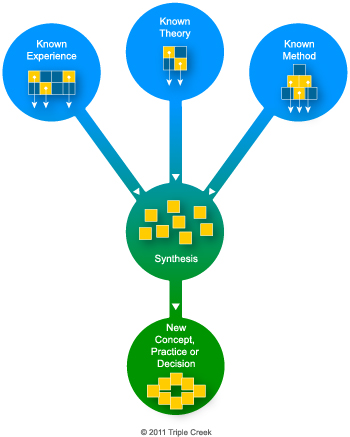

The ability to synthesize is quickly becoming a core competency among knowledge workers. Given all of the aforementioned noise, those people who are able to sift through and synthesize this wealth of information and knowledge into something productive will be well-positioned to be successful in their careers. Likewise, organizations that are able to manage their knowledge and help their employees follow suit will gain a competitive advantage in their respective markets.

Organizations need to be intentional about managing their knowledge in order to do it successfully. Certainly, organizations need to look at their codified knowledge (e.g., methodologies, documented organizational best practices). Knowledge Management Systems have emerged and evolved over the last 20 years or so with varying results, typically modest at best. While there is value in understanding one’s codified knowledge, the effort does not stop there (although unfortunately for some organizations, they assumed it required a “once and done” type of approach).

Beyond categorizing their codified knowledge, organizations need to provide ready access to the tacit knowledge within the organization. By tacit knowledge, I am referring to the “craft know how” that exists in the minds of the individuals who make up the corporation. All organizations have pools of tacit knowledge spread across the entire enterprise, particularly if they rely on knowledge workers for their success. This knowledge is not documented anywhere; it simply resides in the heads of people who have performed well over time. An attempt to codify all of the tacit knowledge in an organization would fail – there is simply too much of it. Instead, organizations should ensure that their employees have easy access to that knowledge through processes such as mentoring. By making employees available to one another for knowledge sharing purposes, organizations can continue to innovate, evolve, and increase the almighty shareholder value.

Beyond categorizing their codified knowledge, organizations need to provide ready access to the tacit knowledge within the organization. By tacit knowledge, I am referring to the “craft know how” that exists in the minds of the individuals who make up the corporation. All organizations have pools of tacit knowledge spread across the entire enterprise, particularly if they rely on knowledge workers for their success. This knowledge is not documented anywhere; it simply resides in the heads of people who have performed well over time. An attempt to codify all of the tacit knowledge in an organization would fail – there is simply too much of it. Instead, organizations should ensure that their employees have easy access to that knowledge through processes such as mentoring. By making employees available to one another for knowledge sharing purposes, organizations can continue to innovate, evolve, and increase the almighty shareholder value.

Simply making knowledge available, however, is insufficient. Smart organizations will help employees become better synthesizers of that available knowledge and information. Helping people with this filtering process is another area where mentoring can play a crucial role. An advisor can assist a learner with understanding which noises to listen to and which to ignore, and subsequently mold the disparate pieces into something of meaning and value.

Synthesis is becoming increasingly valued in the workplace. It is a skill that can be learned, but often takes time, attention, and the expertise of someone who has walked the path before you. Since the great majority of people are not active learners, it is a skill gained through the experience of doing it with deliberate guidance. In too many organizations, the culture is one in which knowledge is hoarded and access is reserved for the organizational elite. You can greatly help your employees become better synthesizers of information by breaking down the barriers of this “old school” culture. Provide employees with open and wide access to the knowledge resources of the enterprise and encourage the practice of mentoring and knowledge sharing at an enterprise level.